Natural history of Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is primarily a respiratory disease (pulmonary TB) caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis, although it can also affect other parts of the body (extra-pulmonary TB). After an infection with TB, 5-10% of individuals develop primary disease within 1-2 years of exposure. The majority of individuals then enter a latent stage in which they passively carry TB mycobacterium. Reactivation of bacilli can then occur many years later due to a loss of immune control [1]. Both active and latent TB cases represent a range of diverse individual states. Pulmonary cases are typically responsible for the vast majority of transmission [2]. Latent cases may have completely cleared the bacterium or be asymptomatically carrying reproducing active TB bacterium [1]. The most common symptoms are a chronic cough with sputum containing blood, fever, night sweats and weight loss. Infectiousness, mortality and likelihood of developing various types of TB vary with age.

Known risk factors

TB has been associated with a large number of risk factors, with HIV being the most powerful. HIV increases the rate of activation by 20 fold and TB is the most common cause of AIDS-related death [3]. In addition to HIV, TB has historically been associated with low socioeconomic status and high density living [4,5]. It has also been found that both smoking and diabetes lead to an increased risk of TB [5], amongst multiple other risk factors such as homelessness, incarceration and drug use [6].

Vaccines

Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) is one of the mostly widely-used vaccines worldwide, with approximately 100m doses given annually [7]. It was first given to humans in 1921 and remains the only licensed vaccine for TB [8]. BCG acts by directly preventing the development of active, symptomatic disease. The effectiveness of the vaccine is effected by the age at which it is given, the latitude of the individual, and the period of time that has lapsed since vaccination. It has consistently been shown to be highly protective in children [9]. Efficacy in adults ranges from 0% to 78% [11]. Multiple randomized control studies have been conducted on BCG efficacy. Meta-analysis of these studies indicates that increased protection is associated with distance from the equator [12]. Meta-analysis has also been used to estimate the waning time of BCG protection. There is good evidence that protection can last up to 10 years and limited evidence of protection beyond 15 years [13].

Due to the variable estimates of BCG efficacy, vaccination has been controversial since its development. Different strategies have been utilized worldwide, including universal vaccination of those at most risk of on-wards transmission and high-risk group vaccination targeting either neonates or children [14]. In 2005, the UK shifted from a strategy of universal vaccination at age 13 years to targeted vaccination in neonates deemed at high risk [15].

Since 2015, BCG vaccination has been included in the Cover Of Vaccination Evaluated Rapidly (COVER) programme, allowing coverage to be estimated in areas of England with universal vaccination (implemented due to high incidence rates). Coverage for areas in England implementing targeted vaccination remains unknown. In London current coverage estimates are made by Local Authority and range from 5.3% to 92.1% [16]. These estimates may not be reliable as COVER has only recently begun to include returns for BCG, meaning that data quality maybe poor.

Treatments

Treatment for TB usually consists of a 6 month course of multiple antibiotics (see Table 1), usually consisting of isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol (known as first line drugs). If the disease is resistant to treatment with the first line drugs then second line drugs such as aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, and cycloserine are employed. The side effects for these drugs are generally far more severe and the treatment regime is longer (12-24 months). The World Health Organisation now recommends the use of the Directly Observed Treatment short-course (DOTS), which focuses on 5 action points [17]. These are:

- Political commitment with increased and sustained financing

- Case detection through quality-assured bacteriology

- Standardized treatment with supervision and patient support

- An effective drug supply and management system

- Monitoring and evaluation system and impact measurement

| Year | Intervention | Type | Line | Detail |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1921 | BCG | Vaccination | The first use of the Bacillus Calmette–Guerin (BCG) vaccine in humans, it remains the only vaccine against Tuberculosis (TB). Efficacy has been shown to vary depending on latitude (0-80%) and there is only strong evidence of protection for 10-15 years after vaccination. | |

| 1944 | Streptomycin | Antibiotic | Second | The first antibiotic and the first bacterial agent against TB. |

| 1944 | 4-Aminosalicylic acid | Antibiotic | Second | The second antiobiotic to be developed. Due to lower potency than other antibiotics it is not considered a first line treatment. |

| 1952 | Isoniazid | Antibiotic | First | Used against both active and latent TB, it may also be given as a prophylatic therapy. |

| 1952 | Cycloserine | Antibiotic | Second | An antibiotic with severe side effects such as kidney failure and neurological conditions, which is therefore restricted for use against multiple drug resistant Tuberculosis. |

| 1952 | Pyrazinamide | Antibiotic | First | First discovered in 1936, it was first used against TB in 1952. Although showing no effect in-vitro it was shown to be effective in treating TB in mice. Used only for treating TB and never on it’s own. |

| 1953 | School age BCG | Vaccination | After a successful trial, which showed high effectiveness for the vaccine, BCG was introduced in the UK for those at school leaving age as peak incidence was then in young, working-adults. | |

| 1962 | Ethambutol | Antibiotic | First | Believed to work by interfering with TB bacteria’s metabolism. There are some concerns that it may not be safe to give during pregancy, as it may lead to vision loss in the baby. |

| 1971 | Rifampicin | Antibiotic | First | Taken daily for at least a period of 6 months, if given alone resistance develops quickly. It may also be used in the treatment of MRSA amongst other diseases. |

| 1995 | DOTS | Strategy | Directly Observed Treatment, Short-Course (DOTS) is introdued by the World Health Organisation as a control strategy for TB. The intermittent, supervised system aims to eliminate drug default. | |

| 2005 | Neonatal high risk BCG | Vaccination | Due to a continued decline in TB incidence rates in the indigenous UK population, the BCG programme was refocused as risk-based. This meant vaccinating high risk neonates rather than those most likely to transmit TB. | |

| 2012 | Bedaquiline | Antibiotic | Second | The first new antiobiotic for use against TB in 40 years, reserved for use against multiple drug resistant TB. Approved via a fast track process, higher mortality in those that recieve the antibiotic has caused significant concern. |

Global TB

TB is a global disease with an estimated 10.4 million new cases in 2015, of which 4.3 million were missed by health systems [17]. TB remains one of the top 10 causes death worldwide, leading to 1.8 million deaths in 2015 alone. Six countries: India, Indonesia, China, Nigeria, Pakistan, and South Africa account for 60% of new cases. India, Indonesia, and Nigeria comprise nearly half of the gap between incident and notified cases. Whilst the absolute number of deaths due to TB has fallen since 2000, the average global rate of decline in TB incidence rates was only 1.4% between 2000-2015. There is an ongoing global co-epidemic of HIV and TB, with people living with HIV accounting for 1.2 million TB cases in 2015. 22% of deaths from TB were in those living with HIV. Multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB), which is defined as being resistant to at least isoniazid and rifampin, made up 4.6% of all new TB cases in 2015 (480,000). It can be acquired both through treatment failure and through transmission. Treatment requires the use of second line antibiotics, which often have more severe side effects and is more likely to fail, with only 52% successfully treated globally compared to 83% for drug susceptible TB [17].

TB in the England and Wales

TB Notifications

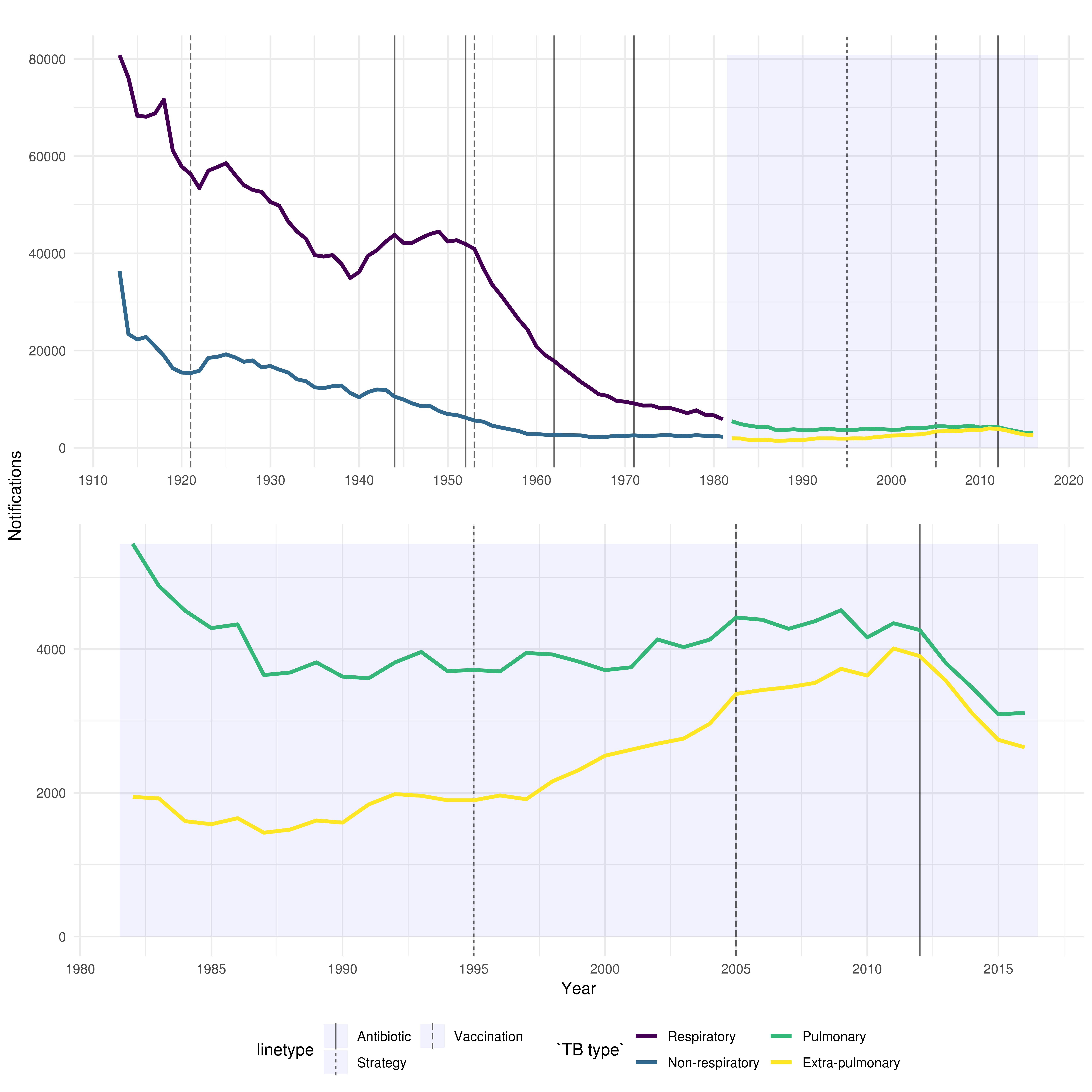

TB incidence in England and Wales has decreased dramatically from a century ago (Figure 1, or see http://www.seabbs.co.uk/shiny/TB_England_Wales for an interactive dashboard). However, in the past several decades, incidence rates have stabilised and have in fact increased since their lowest point in the 1990’s. In 2000 there were 6044 notified TB cases in England, increasing to a maximum of 8280 notified TB cases in 2011. Since then, notifications have declined year on year [18]. Figure 1 includes the interventions discussed above (Table 1) and indicates that the introduction of several antibiotics and BCG vaccination in the 1950’s may have led to an extended decrease in incidence.

Figure 1: TB notifications in England and Wales from 1913 to 2016, stratified initially by respiratory/non-respiratory status and from 1982 by pulmonary/non-pulmonary TB. Interventions are highlighted with vertical lines, with linetype denoting the type of intervention, more information on each intervention is available in the corresponding table

Heterogeneity of TB

TB incidence in the England is highly heterogeneous with over 70% of cases occurring in the non-UK born population. Incidence rates in the non-UK born (49.4 per 100,000, in 2016) are 15 times higher than in the UK born population (3.2 (95% CI 3.0-3.3) per 100,000, in 2016) [16]. The age distribution of cases in the UK born and non-UK born populations differ, with the UK born population having a relatively uniform distribution. Meanwhile, the non-UK born have higher incidence rates in those aged 80 years and older (69.3 per 100,000 in 2016), those aged 75 to 79 years (62.9 per 100,000 in 2016) and those aged 25-29 years old (61.6 per 100,000 in 2016) [16]. In the non-UK born, the majority of cases occur amongst those who have lived in the UK for at least 6 years (63%) - this has increased year on year since 2010 (49%) [16]. However, in 2016, 23.3% (420/1,800) of non-UK born cases had traveled outside the UK, with the majority returning to their country of origin. Incidence rates in the UK born are between 3 and 14 times higher in non-White ethnic groups compared to the White ethnic groups [16].

The majority of cases occur in urban areas with London alone accounting for 39%, with an incidence rate of 25.1 (per 100,000; 95% CI 24.1-26.2; in 2016) [16]. England has few cases of multidrug resistant TB, with only 68 cases in 2016. Similarly the number of co-infections with HIV is low with only 3.8% of cases in 2015 having HIV - the majority of these cases were born in countries with high HIV prevalence. 11.1% of TB cases in 2016 had at least one social risk factor (compared to 11.7% in 2015) [16]. In general cases with social risk factors are more likely to have drug resistant TB, worse TB outcomes and to be lost to follow up [16]. Amongst cases who were of working age in 2016, with a known occupation, 35.2% (1,491/4,240) were not in education or employment, 10.2% (432) were either studying or working in education, and 7.1% (304) were healthcare workers [16].

TB Transmission

As TB incidence rates alone cannot be used to assess current TB transmission, due to reactivation of those latently infected, the incidence rate in UK born children (0-14 years old) is used as a proxy for transmission. Incidence rates in UK born children have fallen 47% from 3.4 per 100,000 in 2008 to 1.8 per 100,000 in 2016 [16]. This indicates that TB transmissions has fallen in the last decade. However, BCG vaccination was introduced for those neonates at high risk of TB in 2005 which maybe partly responsible for the observed reduction in incidence rates.

Strain typing or whole genome sequencing is used to establish case clustering, this can be used to rule out transmission between cases but does not necessarily confirm transmission. Approximately 60% of cases cluster with at least one other case, and whilst this varies year on year, the fluctuations appear to be small (approximately 1-2%) [16]. Therefore interpreting any trend in TB transmission from the current strain typing data is difficult. Between 2010 and 2016, the median cluster size was 3 cases (range 2-244), with 74.4% (2,141/2,878) of clusters consisting of less than 5 cases and only 8.8% of clusters having more than 10 cases [16]. UK born cases were more likely to cluster than non-UK born cases (71.1%, 4,200/5,910 vs. 56.1%, 10,166/18,121) [16].

Pulmonary Vs. Extra-Pulmonary TB

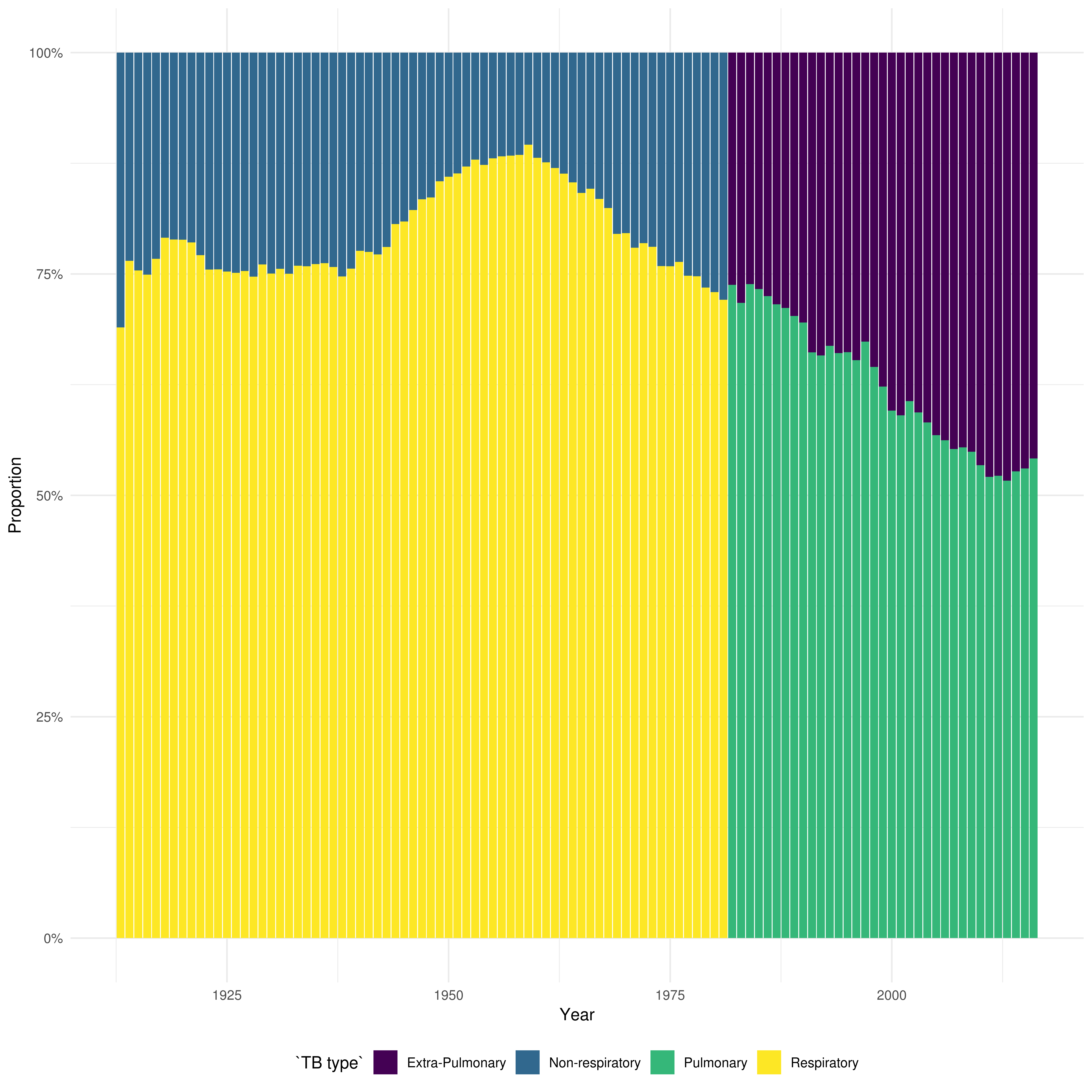

Figure 2 shows that since the 1980’s the proportion of extra-pulmonary TB compared to pulmonary TB has increased from 26.2% (1944/7410) in 1982 to 45.8% (2634/5748) in 2016. This may be attributed to the age distribution of TB cases changing, as different age groups are more likely to progress to pulmonary vs extra-pulmonary TB. It may also be related to the increase of non-UK born cases, as a higher proportion of non-UK born cases have extra-pulmonary disease only (51.4%, 2,103/4,089, in 2016), compared to UK born cases (31.9%, 467/1,465, in 2016) [16]. For more details on TB in England see the Public Health England 2017 TB report, from which the summary data discussed above was extracted [16].

Figure 2: From 1913 until 1981 the figure shows the proportion respiratory vs. non-respiratory cases and from 1982 it shows the proportion of pulmonary vs. non-pulmonary TB.

References

1 Gideon HP, Flynn JL. Latent tuberculosis: What the host "sees"? Immunol Res 2011;50:202–12. doi:10.1007/s12026-011-8229-7

2 Sepkowitz K a. How contagious is tuberculosis? Clin Infect Dis 1996;23:954–62. doi:10.1093/clinids/23.5.954

3 Rottenberg ME, Pawlowski A, Jansson M et al. Tuberculosis and HIV Co-Infection. 2012;8. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002464

4 Bhatti N, Law MR, Morris JK et al. Increasing incidence of tuberculosis in England and Wales: a study of the likely causes. BMJ 1995;310:967–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.310.6985.967

5 Narasimhan P, Wood J, Macintyre CR et al. Risk Factors for Tuberculosis. 2013;2013.

6 Story A, Murad S, Roberts W et al. Tuberculosis in London: the importance of homelessness, problem drug use and prison. 2007;667–72. doi:10.1136/thx.2006.065409

7 The World Health Organization. BCG Vaccine. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2004;79:27–48.

8 Medicine C. History of BCG Vaccine. 2013;8:53–8.

9 Rodrigues LC, Diwan VK, Wheeler JG. Protective effect of BCG against tuberculous meningitis and miliary tuberculosis: a meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol 1993;22:1154–8.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8144299

10 Colditz GA, Brewer TF, Berkey CS et al. Efficacy of BCG Vaccine in the Prevention of Tuberculosis. JAMA 1994;271:698. doi:10.1001/jama.1994.03510330076038

11 Mangtani P, Abubakar I, Ariti C et al. Protection by BCG Vaccine Against Tuberculosis: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin Infect Dis 2014;58:470–80. doi:10.1093/cid/cit790

12 Mangtani P, Abubakar I, Ariti C et al. Protection by BCG vaccine against tuberculosis: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis 2014;58:470–80. doi:10.1093/cid/cit790

13 Abubakar I, Pimpin L, Ariti C et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the current evidence on the duration of protection by bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccination against tuberculosis. Health Technol Assess (Rockv) 2013;17:1–372, v–vi. doi:10.3310/hta17370

14 Zwerling A, Behr MA, Verma A et al. The BCG world atlas: A database of global BCG vaccination policies and practices. PLoS Med 2011;8. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001012

15 Public Health England. The Green Book. 2013;391–409.

16 Public Health England. Tuberculosis in England 2017 report ( presenting data to end of 2016 ) About Public Health England. 2017.

17 World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report. 2016.

18 PHE. Tuberculosis in England 2016 Report (presenting data to end of 2015). Public Heal Engl 2016;Version 1.:173.